The Unbelievable Story of the Paris Catacombs

January 24, 2023

Want to see the creepiest attraction in Paris?

By the middle of the 18th century, Paris stunk. It may have been one of the largest and most prosperous cities in the Western World but its own rapid growth was causing the city’s cemeteries to literally overflow with the bodies of the dead. The reek of decomposing flesh attained epidemic proportions in certain areas of the city, including, most troublingly, the area around the main food market of Les Halles.

With public health at risk, something had to be done, but few expected that the solution would create one of the most singular and spooky tourist attractions in the world. It was an incredible feat of architectural derring-do, marketing genius, and downright hard, nasty work that helped turn the city from a stinking, pestilent warren of medieval chaos into one of the most beautiful and progressive cities in Europe.

It’s a story of progress, of foresight, and a bit of macabre interior design. It’s the story of the Paris Catacombs.

Paris had a BIG problem with its dead

The cemetery of the Innocents – the largest and most important within Paris’ city limits – contained some 2 million bodies. Once you included the rest of the city cemeteries the count came to roughly 6 million sets of remains that needed to be disinterred and reburied somewhere else for the greater public good. Given the religious nature of the original burials, they could not simply be dug up and thrown around willy nilly, either – they would have to be re-buried with some form of ritual in one of the largest transmissions of human remains in history.

Stones for the living provided the space for the dead

Fortuitously for the nascent Paris Catacombs project, the city sat directly above some 200 miles of limestone tunnels that had been carved out to provide the very stones from which the city was built. The tunnels were so extensive that by the 19th century the weight of the city above was creating giant sinkholes into which entire buildings and blocks were collapsing.

In 1777 the King’s architect Charles-Axel Guillaumot was given the unenviable task of stabilizing the entire system of subterranean mine shafts in order to literally save the city from collapse. No pressure, then. Despite the size of the challenge, Guillaumot pulled it off without much fuss.

By 1785 the tunnels were stable and the remains of dead Parisians were being dug up every night and transferred into them. A priest accompanied every wagonload of remains in order to chant the Catholic “Office of the Dead” prayer cycle to ensure that the remains remained at peace.

Royalty made the Paris Catacombs but Napoleon made them a tourist attraction

It took two years of nightly work to empty the majority of Paris’ cemeteries and relocate the remains in the catacombs, but the transfer of bones continued up until 1859. Above ground, public works went on hold for a few years while France had a revolution, executed a lot of people, and then slowly started to rebuild.

When Napoleon marched to power on the back of the Revolution he inherited a medieval city that was in the throws of rapid modernization. One of the Little Emperor’s key beliefs was that “men are only great through the monuments they leave behind them.” In this vein, he punctuated his reign with a number of grandiose public works and pieces of art (like Jacques-Louis David’s Coronation of Napoleon), many of which helped to give rise to the concept of the “Napoleon complex”.

Given that Rome, which was considered the preeminent monumental city in Europe, already had its much-vaunted system of Catacombs that intrepid tourists could visit, Napoleon decided that France needed something similar. He commissioned his Prefect of the Seine, Nicolas Frochot, and the Inspector-General of the quarries, Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury, to turn the quarry tunnels from a labyrinthine charnel house into something that people would want to go down and see, thus giving rise to the original Paris Catacombs tours.

The bone decorations were created specifically to attract tourists, and they were very successful

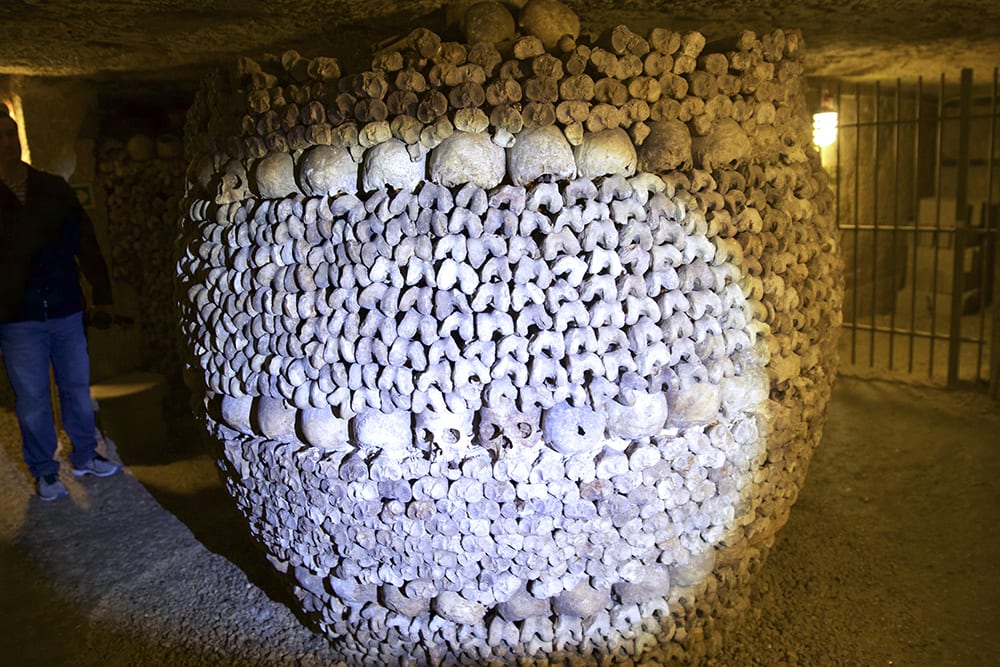

When quarry-men, under the direction of Héricart de Thury, began arranging the transferred bones into ossuary decorations they had their work cut out for them. Despite the ritual with which they were transferred, the bones had simply been dumped into the tunnels in large heaps.

Slowly but surely the quarrymen lined the walls with tibias and femurs punctuated with skulls which form the basis of most of the decorations that tourists see today. Both out of whimsy and to convey deeper religious messages about death, they also arranged bones in various shapes, like hearts, circles and death heads. They erected signs which serve as commemorative plaques and carved arrows into the ceilings so the first people visiting on catacomb tours (who were seeing everything by the eerie flicker of candlelight) would not lose their way.

This didn’t stop a group of 25 English tourist from getting lost in 1903; they all got out safely though, eventually. Through these changes, and a clever marketing brochure published by Héricart de Thury in 1810, the Paris catacombs soon gained a reputation as one of the more affecting, and surely the most macabre place to visit in the city.

Occasionally the Paris Catacombs host parties

Not legal ones, mind you. There is a persistent rumor that the Comte d’Artois, who later ruled France briefly as Charles X, used to hold clandestine parties in the Catacombs. Although it’s hard to verify the truth of that claim, on April 2, 1897, a group of amateur musicians staged an impromptu, and highly illegal, concert in the Catacombs late at night for about 100 people.

The program included Chopin’s Funeral March and Camille Saint-Saens’ Danse Macabre. One problem caused by the influx of visitors, both legal and illegal, was that skulls began to mysteriously vanish from their alcoves. Initially, quarry workers replaced them with new skulls but they eventually stopped. Today, every time you see a gap in a line of skulls, just remember that someone probably took that one home with them as a souvenir.

It’s not just bones decorating the Paris Catacombs

In order to entice more visitors, various “exhibitions” were installed in the Catacombs. These included a room showcasing skeletons with various deformities as well as a room displaying the types of minerals that were found when the tunnels were being excavated – neither of which you can see anymore.

Goldfish were brought in and dropped into a little pool called the Samaritan Fountain. Although the fountain, which collects ground water, is still a feature of the Catacombs, the fish are long dead – turns out goldfish don’t exactly thrive underground.

The most enduring of the Paris Catacomb’s exhibits are a series of stone carvings created by a slightly mysterious figure called Decuré. He was a veteran of the French army and a spent some time in Minorca when the French annexed the Island from the British.

When not helping his fellow quarrymen stabilize the tunnels, he carved faithful renderings of the Citadel of Mahon as well as other important buildings from that island. They are incongruous, unexpected, and not really connected to anything, but fascinating nonetheless. Decuré was killed in a rock fall while working in the Catacombs – no word on where he was buried.

by Walks of Italy

View more by Walks ›Book a Tour

Pristine Sistine - The Chapel at its Best

€89

1794 reviews

Premium Colosseum Tour with Roman Forum Palatine Hill

€56

850 reviews

Pasta-Making Class: Cook, Dine Drink Wine with a Local Chef

€64

121 reviews

Crypts, Bones Catacombs: Underground Tour of Rome

€69

401 reviews

VIP Doge's Palace Secret Passages Tour

€79

18 reviews

Legendary Venice: St. Mark's Basilica, Terrace Doge's Palace

€69

286 reviews